Today at Noon Rounds, we talked about the management of Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) and Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar State (HHS).

Please click on the link below to read an oldie-but-goodie post regarding this topic:

http://morningreportmsh.blogspot.ca/2012/07/diabetic-ketoacidosis.html

The following is a nice schematic diagram outlining the initial management of patients with DKA and HHS from the American Diabetes Association Consensus Statement on Hyperglycemic Crises in Adult Patients With Diabetes. (Hint: click on the picture to make it bigger). Reference: Kitabchi AE et al., Diabetes Care. 2009;32(7):1335-1343.

Lastly, what's a post on diabetes and glycemic control without reference to the two landmark trials that changed the landscape of glycemic control for patients with type 1 (DCCT and it's follow-up trial, EDIC) and type 2 (UKPDS) diabetes. For your reference, please click on the links to read these important trials.

1) Diabetes Control and Complications Trial, NEJM (1993)

2) Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Trial, NEJM (2005)

3) United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study, Lancet (1998)

Tuesday, July 31, 2012

Thursday, July 26, 2012

Severe Sepsis

Today at Noon Rounds, we learned about the management of severe sepsis.

Remember, the enigmatic "sepsis" fits within a spectrum of disease:

1) SIRS (systematic inflammatory response syndrome) = at least 2 of a) temperature >38.3ºC or <36ºC, b) pulse >90 bpm, c) RR>20 breaths/min or PaCO2<32 mmHg, and d) WBC>12 or <4

2) Sepsis = SIRS + source of infection

3) Severe sepsis = Sepsis + end-organ dysfunction (including CNS, renal, cardiac, respiratory, hematologic)

4) Septic shock = Severe sepsis + inability to respond to adequate fluid resuscitation

The "Surviving Sepsis Campaign" is an international campaign designed to raise awareness and streamline the management of this important syndrome, which still carries with it a 30-day mortality rate of approximately 30%.

Click on this link for the full set of guidelines published in Critical Care Medicine in 2008, and on this link for the handy-dandy pocket guide.

These Guidelines are based, in part, upon the "Rivers Protocol" or Early-Goal Directed Therapy, published in NEJM in 2001. Click here to read this seminal paper.

In addition to these important hemodynamic parameters, we must not forget about treating the source of sepsis. This typically means identification of the source of infection and early and appropriate broad-spectrum antibiotics (within one-hour of identification of severe sepsis, and ideally after cultures have been drawn) +/- source control.

Remember, the enigmatic "sepsis" fits within a spectrum of disease:

1) SIRS (systematic inflammatory response syndrome) = at least 2 of a) temperature >38.3ºC or <36ºC, b) pulse >90 bpm, c) RR>20 breaths/min or PaCO2<32 mmHg, and d) WBC>12 or <4

2) Sepsis = SIRS + source of infection

3) Severe sepsis = Sepsis + end-organ dysfunction (including CNS, renal, cardiac, respiratory, hematologic)

4) Septic shock = Severe sepsis + inability to respond to adequate fluid resuscitation

The "Surviving Sepsis Campaign" is an international campaign designed to raise awareness and streamline the management of this important syndrome, which still carries with it a 30-day mortality rate of approximately 30%.

Click on this link for the full set of guidelines published in Critical Care Medicine in 2008, and on this link for the handy-dandy pocket guide.

These Guidelines are based, in part, upon the "Rivers Protocol" or Early-Goal Directed Therapy, published in NEJM in 2001. Click here to read this seminal paper.

In addition to these important hemodynamic parameters, we must not forget about treating the source of sepsis. This typically means identification of the source of infection and early and appropriate broad-spectrum antibiotics (within one-hour of identification of severe sepsis, and ideally after cultures have been drawn) +/- source control.

Monday, July 23, 2012

Bacterial Meningitis

During Noon Rounds on Friday, we discussed the importance of recognizing and treating bacterial meninigits, a diagnosis that still carries with it a case-fatality rate of 16.4%! (Please visit this link to connect you to the 2007 NEJM article detailing surveillance data on culture-confirmed cases of bacterial meningitis in the United States from 1998-2007).

To review, the classic triad consists of: fever, nuchal rigidity, and altered mental status. Remember, many patients do not present with all three features, but most will present with at least one.

Jolt accentuation of headache is the most sensitive maneuver for detecting meningitis.

The common culprit bugs include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and, primarily in patients over age 50 or those who have deficiencies in cell-mediated immunity, Listeria monocytogenes.

Knowing this, first-line empiric antimicrobial therapy consists of:

1) ceftriaxone 2 g iv q12h

2) vancomycin 1 g iv q8h

3) ampicillin 2 g iv q4h (in those patients where Listeria monocytogenes is a consideration)

In those patient's where Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis is a consideration, give dexamethasone 0.15 mg/kg iv q6h for four days, with the first dose given 15-20 minutes prior to or at the time of antibiotic administration.

Please visit the following link to view the Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Bacterial Meningitis.

Friday, July 20, 2012

Decompensated Heart Failure

Today in Morning Report, we walked through a case of decompensated heart failure.

We learned that it is not only important to treat decompensated heart failure by decreasing preload and afterload, but it is equally important to look for the precipitant of decompensation.

Medications (either changes in doses, additions, or discontinuations, top culprits include NSAIDS, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, beta-blockers, CCBs)

Dietary indiscretion

Iatrogenic volume overload (read: the "unnecessary" continuous intravenous fluid infusion)

Cardiac

- Valvular disease (e.g. aortic stenosis or acute or progressive mitral regurgitation)

- Myocardial infarction and myocardial ischemia

- Progression of underlying cardiac dysfunction

- Cardiomyopathy (inherited, such as HOCM, vs acquired, such as Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and cardiotoxic agents such as alcohol, cocaine, and some chemotherapeutic agents, like anthracyclines)

- Arrythmias (e.g. atrial fibrillation, and less commonly, atrial flutter, sinus tachycardia, other supraventricular tachycardias, and ventricular tachycardia)

Severe hypertension (increasing afterload)

Renal failure

Infections (e.g. UTIs, pneumonia)

Anemia

Metabolic (e.g. hypo- or hyperthyroidism)

Pulmonary embolism

Click here for a link to the 2009 Canadian Cardiovascular Society consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of right-sided heart failure.

Thursday, July 19, 2012

A Tale of Three Cases

Today in Rapid Fire Morning Report, we discussed three interesting and different cases that showcase the wonderful depth and breadth that Internal Medicine has to offer. And, now, a Tale of Three Cases:

1) Proton Pump Inhibitors and Upper GI Bleeding

- There is a lot of evidence supporting acid suppression in the setting of bleeding peptic ulcers.

- However, oral dosing of PPIs has not been directly compared with high-dose intravenous therapy.

- A meta-analysis of five trials evaluating oral PPIs found a significant reduction in the risk of recurrent bleeding and surgery compared with treatment with placebo or an H2-receptor antagonist.

- High-dose PPIs given orally achieve adequate acid suppression more rapidly than standard doses. And, high-dose intravenous PPIs achieve adequate acid suppression more rapidly than high-dose oral PPIs. Whether this leads to any appreciable difference on hard clinical outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality is still up in the air.

2) Acute Exacerbation of Bronchiectasis

- Antibiotics are used to treat acute exacerbations of bronchiectasis and prevent recurrent infections by minimizing or erradicating the existing bugs that colonize bronchiectatic airways.

- These problematic bugs include Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Hemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), and Aspergillus species (see the "Diagnosis Aspergillosis" post for more information).

- Diagnosed clinically: increased sputum production, change in sputum colour, dyspnea. Fever and CXR findings are not always found.

- A good first-line option for treatment of an uncomplicated exacerbation in the outpatient setting is a fluoroquinolone (e.g. ciprofloxicin).

- Consideration can be made to include dual anti-Pseudomonal coverage for treatment of exacerbations in the inpatient setting.

- Always consider and tailor antimicrobial therapy to previous cultures and sensitivities if they are available.

3) HIV-associated Diarrhea

- The differential diagnosis of diarrhea in a patient with HIV is long(!)

- But, don't be overwhelmed. Always remember your ABCs first. Resuscitate the patient. Then, you will have time to think through your workup and management plan.

- Always take into account their immunologic status (what is the CD4 count?)

- Broadly speaking, the diagnosis typically fits into one of the following categories:

Infectious (the regular stuff, such as E. coli, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Clostridium, etc., as well as the opportunistic bugs, such as CMV, cryptosporidia, microsporidia...and HIV itself)

Malignancy (e.g. Kaposi sarcoma, lymphoma)

Drugs (e.g. ritonavir)

- Send the stool for culture and sensitivity, ova and parasites, and C. difficile toxin. Consider blood cultures, blood for AFB and CMV antigenemia, and abdominal imaging.

- Consider asking for expert advice from our colleagues in Gastroenterology and/or Infectious Diseases.

That's right. All in a night's work.

1) Proton Pump Inhibitors and Upper GI Bleeding

- There is a lot of evidence supporting acid suppression in the setting of bleeding peptic ulcers.

- However, oral dosing of PPIs has not been directly compared with high-dose intravenous therapy.

- A meta-analysis of five trials evaluating oral PPIs found a significant reduction in the risk of recurrent bleeding and surgery compared with treatment with placebo or an H2-receptor antagonist.

- High-dose PPIs given orally achieve adequate acid suppression more rapidly than standard doses. And, high-dose intravenous PPIs achieve adequate acid suppression more rapidly than high-dose oral PPIs. Whether this leads to any appreciable difference on hard clinical outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality is still up in the air.

2) Acute Exacerbation of Bronchiectasis

- Antibiotics are used to treat acute exacerbations of bronchiectasis and prevent recurrent infections by minimizing or erradicating the existing bugs that colonize bronchiectatic airways.

- These problematic bugs include Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Hemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), and Aspergillus species (see the "Diagnosis Aspergillosis" post for more information).

- Diagnosed clinically: increased sputum production, change in sputum colour, dyspnea. Fever and CXR findings are not always found.

- A good first-line option for treatment of an uncomplicated exacerbation in the outpatient setting is a fluoroquinolone (e.g. ciprofloxicin).

- Consideration can be made to include dual anti-Pseudomonal coverage for treatment of exacerbations in the inpatient setting.

- Always consider and tailor antimicrobial therapy to previous cultures and sensitivities if they are available.

3) HIV-associated Diarrhea

- The differential diagnosis of diarrhea in a patient with HIV is long(!)

- But, don't be overwhelmed. Always remember your ABCs first. Resuscitate the patient. Then, you will have time to think through your workup and management plan.

- Always take into account their immunologic status (what is the CD4 count?)

- Broadly speaking, the diagnosis typically fits into one of the following categories:

Infectious (the regular stuff, such as E. coli, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Clostridium, etc., as well as the opportunistic bugs, such as CMV, cryptosporidia, microsporidia...and HIV itself)

Malignancy (e.g. Kaposi sarcoma, lymphoma)

Drugs (e.g. ritonavir)

- Send the stool for culture and sensitivity, ova and parasites, and C. difficile toxin. Consider blood cultures, blood for AFB and CMV antigenemia, and abdominal imaging.

- Consider asking for expert advice from our colleagues in Gastroenterology and/or Infectious Diseases.

That's right. All in a night's work.

Wednesday, July 18, 2012

Lymphadenopathy

Today in Morning Report, we discussed the differential diagnosis of lymphadenopathy. Broadly, one should consider the following etiologies:

- Infectious (bacterial, viral, mycobacterial, fungal, protozoal, spirochete)

- Malignancy (primary vs. metastatic; hematologic vs. solid)

- Lymphoproliferative (hemophagocytic lymphohistiosis)

- Immunologic (serum sickness, drug reactions)

- Endocrine (hypothyroid, Addison's)

- Other (sarcoidosis, SLE, rheumatoid arthritis)

When you first approach such a presentation, it is important to differentiate between localized and generalized lymphadenopathy.

Localized lymphadenopathy involves typically only one of the following lymph node regions:

Cervical: systemic infection (EBV, CMV, toxoplasmosis,TB), lymphoma, head and neck malignancy.

Supraclavicular: right-sided (associated with thoracic malignancies), left-sided/"Virchow' node" (associated with intraabdominal malignancies).

Axillary: local infection (cat scratch disease), malignancy (breast).

Epitrochlear: palpable epitrochlear lymph nodes are always pathologic, differential diagnosis includes infection, lymphoma, sarcoidosis, secondary syphillis.

Inguinal: lower extremity infection, STIs, malignancy.

Generalized lymphadenopathy is commonly a feature of a systemic disease, including:

HIV: in acute, primary infection, typically non-tender.

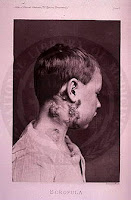

Mycobacterial infection (tuberculous and non-tuberculous): called "scrofula" when it involves lymph nodes alone, typically the neck.

Infectious mononucleosis: classic triad of fever, lymphadenopathy, and pharyngitis.

SLE: more frequently noted in acute presentation or exacerbation of disease.

Medications: often associated with "serum sickness" (fever, arthralgias, rash, generalized lymphadenopathy), e.g. allopurinol, atenolol, antiepileptics, hydralazine.

Uncommon causes include: Castleman's disease, Kikuchi's disease, Kawasaki disease, amyloidosis.

A lymph node biopsy:

- can be considered if an abnormal node has not resolved after four weeks.

- should be performed immediately in patients with other findings suggesting malignancy (fever, chills, night sweats, unintentional weight loss).

- open lymph node biopsy is preferred, if feasible.

Check out this NEJM Images in Clinical Medicine for a less than subtle presentation of axillary lymphadenopathy: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMicm071065.

- Infectious (bacterial, viral, mycobacterial, fungal, protozoal, spirochete)

- Malignancy (primary vs. metastatic; hematologic vs. solid)

- Lymphoproliferative (hemophagocytic lymphohistiosis)

- Immunologic (serum sickness, drug reactions)

- Endocrine (hypothyroid, Addison's)

- Other (sarcoidosis, SLE, rheumatoid arthritis)

When you first approach such a presentation, it is important to differentiate between localized and generalized lymphadenopathy.

Localized lymphadenopathy involves typically only one of the following lymph node regions:

Cervical: systemic infection (EBV, CMV, toxoplasmosis,TB), lymphoma, head and neck malignancy.

Supraclavicular: right-sided (associated with thoracic malignancies), left-sided/"Virchow' node" (associated with intraabdominal malignancies).

Axillary: local infection (cat scratch disease), malignancy (breast).

Epitrochlear: palpable epitrochlear lymph nodes are always pathologic, differential diagnosis includes infection, lymphoma, sarcoidosis, secondary syphillis.

Inguinal: lower extremity infection, STIs, malignancy.

Generalized lymphadenopathy is commonly a feature of a systemic disease, including:

HIV: in acute, primary infection, typically non-tender.

Mycobacterial infection (tuberculous and non-tuberculous): called "scrofula" when it involves lymph nodes alone, typically the neck.

Infectious mononucleosis: classic triad of fever, lymphadenopathy, and pharyngitis.

SLE: more frequently noted in acute presentation or exacerbation of disease.

Medications: often associated with "serum sickness" (fever, arthralgias, rash, generalized lymphadenopathy), e.g. allopurinol, atenolol, antiepileptics, hydralazine.

Uncommon causes include: Castleman's disease, Kikuchi's disease, Kawasaki disease, amyloidosis.

A lymph node biopsy:

- can be considered if an abnormal node has not resolved after four weeks.

- should be performed immediately in patients with other findings suggesting malignancy (fever, chills, night sweats, unintentional weight loss).

- open lymph node biopsy is preferred, if feasible.

Check out this NEJM Images in Clinical Medicine for a less than subtle presentation of axillary lymphadenopathy: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMicm071065.

Friday, July 13, 2012

Overdose!

I thought I'd take the opportunity to review one of the most common toxidromes we encounter in the world of Internal Medicine, the anticholinergic toxidrome.

Common anticholinergic medications include:

- antihistamines (e.g. diphenhydramine/Benadryl)

- antiemetics (e.g. dimenhydramine/Gravol)

- tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline, nortriptyline)

- scopolamine

- "contaminated" recreational drugs (e.g. heroin cut with scopolamine)

- atropine

- neuroleptics (e.g. quetiapine/Seroquel, clozapine, olanzapine/Zyprexa)

- antiparkinson medications (e.g. benztropine)

Anticholinergic drugs competitively inhibit binding of acetycholine to muscarinic cholinergic receptors found in smooth muscle (GI, bronchial, cardiac), secretory glands (salivary, sweat), ciliary body of eye, and the CNS.

Knowing this makes for remember this classic description of anticholinergic toxicity easy as pie:

"Red as a beet" - cutaneous vasodilation

"Dry as a bone" - dry skin

"Hot as a hare" - interference with sweat production interupts thermoregulation

"Blind as a bat" (nonreactive mydriasis) - pupillary dilation and ineffective accomodation = blurry vision

"Mad as a hatter" (delirium, hallucinations) - CNS symptoms of muscarinic blockade, which to the extreme, may result in seizure or coma

"Full as a flask" (urinary retention) - relaxation of detrusor muscle and constriction of urethral sphincter

The fundamental principles of management include:

- Call the Poison Control Centre.

- Stabilize the patient's ABCs.

- Supportive care and cardiorespiratory monitoring.

- Sodium bicarbonate in the setting of QT interval prolongation.

- Treatment of seizures and/or aggitation with benzodiazepines (e.g. lorazepam); do NOT use antipsychotic medications, as these may further prolong an already prolonged QT interval.

- Consideration of physostigmine, an antidote that is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that binds reversibly to inhibit acetylcholinesterase in both the peripheral and central nervous system. It's usage is controversial, and no studies have demonstrated its efficacy or safety to date.

Common anticholinergic medications include:

- antihistamines (e.g. diphenhydramine/Benadryl)

- antiemetics (e.g. dimenhydramine/Gravol)

- tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline, nortriptyline)

- scopolamine

- "contaminated" recreational drugs (e.g. heroin cut with scopolamine)

- atropine

- neuroleptics (e.g. quetiapine/Seroquel, clozapine, olanzapine/Zyprexa)

- antiparkinson medications (e.g. benztropine)

Anticholinergic drugs competitively inhibit binding of acetycholine to muscarinic cholinergic receptors found in smooth muscle (GI, bronchial, cardiac), secretory glands (salivary, sweat), ciliary body of eye, and the CNS.

Knowing this makes for remember this classic description of anticholinergic toxicity easy as pie:

"Red as a beet" - cutaneous vasodilation

"Dry as a bone" - dry skin

"Hot as a hare" - interference with sweat production interupts thermoregulation

"Blind as a bat" (nonreactive mydriasis) - pupillary dilation and ineffective accomodation = blurry vision

"Mad as a hatter" (delirium, hallucinations) - CNS symptoms of muscarinic blockade, which to the extreme, may result in seizure or coma

"Full as a flask" (urinary retention) - relaxation of detrusor muscle and constriction of urethral sphincter

The fundamental principles of management include:

- Call the Poison Control Centre.

- Stabilize the patient's ABCs.

- Supportive care and cardiorespiratory monitoring.

- Sodium bicarbonate in the setting of QT interval prolongation.

- Treatment of seizures and/or aggitation with benzodiazepines (e.g. lorazepam); do NOT use antipsychotic medications, as these may further prolong an already prolonged QT interval.

- Consideration of physostigmine, an antidote that is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that binds reversibly to inhibit acetylcholinesterase in both the peripheral and central nervous system. It's usage is controversial, and no studies have demonstrated its efficacy or safety to date.

- Consideration of activated charcoal depending on the timing of the ingestion, and the patient's level of consciousness.

Thursday, July 12, 2012

Rapid Fire Morning Report

Since we had the fortune of hearing about three such fascinating cases this morning, I thought I would take the opportunity to briefly review each of these diagnoses in turn:

1) Polymyalgia Rheumatica (PMR)

- It is a disease of adults. Occurs almost exclusively in those over the age of 50. The average age at diagnosis is 70.

- Presents with aching and morning stiffness greater than 30 minutes in the hip and shoulder girdles, neck, and torso.

- Does NOT typically present with muscle weakness.

- Associated with giant cell arteritis (GCA)/temporal arteritis. PMR occurs in about 50 percent of patients with GCA, while approximately 15 to 30 percent of patients with PMR eventually develop GCA.

- Diagnostic criteria includes an ESR>40 mm/h, although we typically see ESR in excess of 100 mm/h.

- Prompt response of symptoms with 24 hours to low-dose glucocorticoids (e.g. prednisone 15 mg daily) is classically seen.

Follow the link below for a review article on "Polymyalgia Rheumatica and Giant Cell Arteritis" from NEJM (2002):

2) Massive Hemoptysis

- Always remember your ABCs! Stabilize the patient first. Do not hesitate to ask for help.

- The differential diagnosis includes:

Bronchiectasis

Tuberculosis

Fungal infections (e.g. aspergillosis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis)

Lung infection/abscess

Malignancy (especially bronchogenic carcinoma)

Autoimmune lung disease (e.g. pauciimmune vasculitidies, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis/Wegener's granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis; Goodpasture's syndrome; SLE)

Pulmonary AVM (such as in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia)

Mitral stenosis

PE

3) Optic Neuropathies

- Clinical features include vision loss, eye pain, RAPD in the affected eye, central scotoma. Remember, findings may not be apparent upon fundoscopy if the disease is retrobulbar.

- The differential diagnosis is broad, and includes:

Optic neuritis (inflammatory demyelinating process that can be idiopathic, or also associated with multiple sclerosis or neuromyelitis optica)

Ischemic optic neuropathy (common in older patients with vascular risk factors)

Infections (including neurosyphyllis, Lyme disease, West Nile virus)

Sarcoidosis

Autoimmune disease (such as SLE, Sjogren's)

Paraneoplasic causes

Malignancy (such as mass effect)

Drugs and toxins (such as ethambutol)

- Prompt investigations (such as imaging, LP) and referral to the appropriate specialties (such as Ophthalmology, Neurology, Neurosurgery) is of utmost importance.

Click on the link for review article on "Optic Neuritis" from NEJM (2006):

Wednesday, July 11, 2012

Altered Mental Status in the Elderly

We learned in Morning Report today that medications are the top culprit when it comes to altered mental status in the elderly population.

The "Beers List" is a consensus list of potentially inappropriate medications for older persons published by the American Geriatrics Society. It was first published in 1991, and most recently updated in 2012.

The "Beers List" is a consensus list of potentially inappropriate medications for older persons published by the American Geriatrics Society. It was first published in 1991, and most recently updated in 2012.

Please click on the following link for a copy of the paper:

These high risk medications include, but are not limited to drugs in the following broad categories (with examples that follow in brackets):

- Anticholinergics (antihistamines)

- Antiparkinson agents (benztropine)

- Antispasmodics (hyocyamine or Buscopan)

- Antithrombotics

- Antihypertensives (alpha and/or beta blockers)

- Antiarrythmic drugs (amiodarone)

- Antipsychotic drugs

- Barbituates

- Benzodiazepines

- Nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics (zopiclone)

- Insulin

- Hormone therapy (androgen, estrogen)

- Analgesic agents (opioids, NSAIDS)

- Skeletal muscle relaxants (cyclobenzaprine or Flexeril)

There was mention in passing about the purported influence of digitalis toxicity on Van Gogh's works of art later in life, which were characterized by halos and the colour yellow. Click on the link below for a fascinating paper published in JAMA in 1981 entitled, "Van Gogh's Vision: Digitalis Intoxication?":

And, last, but certainly not least, in order to make your Morning Report experience greater than it is already (if that's even possible), please click the link below for Dr. Detsky's guide for "Taking the Stress out of Morning Report":

Tuesday, July 10, 2012

Diagnosis Aspergillosis

Today in Morning Report, we simplified the hocus pocus surrounding the diagnosis of aspergillosis.

The term "aspergillosis" refers to illness due to allergy, airway or lung invasion, cutaneous infection, or extrapulmonary dissemination caused by species of Aspergillus, which is ubiquitous in nature, and commonly transmitted via inhalation of fungal conidia.

These conidia then face the innate defenses of alveolar phagocytes and the activation of cellular immunity, which are important in the healthy host for preventing fungal invasion in the surrounding tissue, and determining the extent and nature of the immune response.

There are four common syndromes by which aspergillosis manifests:

1) Aspergilloma (fungal ball)

2) Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (hypersensitivity reaction of the airways that occurs when bronchi become colonized by Aspergillus species commonly seen in patients with a history of asthma)

3) Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis

4) Invasive Aspergillosis

To elaborate on the fourth, and most worrisome manifestation of asperillosis:

- Characterized by progression of the infection across tissue planes, eventually leading to vascular invasion with subsequent infarction and tissue necrosis.

- Classic risk factors include neutropenia, exogenous glucocorticoids, and impaired cellular immune function (e.g. AIDS, immunosuppresive medications).

- Signs and symptoms include fever, chest pain, shortness of breath, cough, and/or hemoptysis.

- Remember, neutropenic patients frequently present with fever in the absence of localizing pulmonary symptoms.

- Pulmonary aspergillosis typically manifests as single or multiple nodules with or without cavitation, patchy or segmental consolidation, or peribronchial infiltrates, with or without tree-in-bud patterns.

- In the presence of angioinvasive disease, Aspergillus species can hematogenously spread to the skin, brain, eyes, liver, and kidneys. This obviously portends a poor prognosis.

- To diagnosis invasive aspergillosis, consider initially sending serum biomarkers, such as galactomannan, and obtaining sputum for fungal staining and culture.

- If the diagnosis is not made, more invasive options include bronchoscopy, image-guided needle biopsy, or video-assisted thorascopic surgery.

- The recommended intial therapy is voriconazole, or lipophilic amphotericin B if there is a contraindication to voriconazole.

The term "aspergillosis" refers to illness due to allergy, airway or lung invasion, cutaneous infection, or extrapulmonary dissemination caused by species of Aspergillus, which is ubiquitous in nature, and commonly transmitted via inhalation of fungal conidia.

These conidia then face the innate defenses of alveolar phagocytes and the activation of cellular immunity, which are important in the healthy host for preventing fungal invasion in the surrounding tissue, and determining the extent and nature of the immune response.

There are four common syndromes by which aspergillosis manifests:

1) Aspergilloma (fungal ball)

2) Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (hypersensitivity reaction of the airways that occurs when bronchi become colonized by Aspergillus species commonly seen in patients with a history of asthma)

3) Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis

4) Invasive Aspergillosis

To elaborate on the fourth, and most worrisome manifestation of asperillosis:

- Characterized by progression of the infection across tissue planes, eventually leading to vascular invasion with subsequent infarction and tissue necrosis.

- Classic risk factors include neutropenia, exogenous glucocorticoids, and impaired cellular immune function (e.g. AIDS, immunosuppresive medications).

- Signs and symptoms include fever, chest pain, shortness of breath, cough, and/or hemoptysis.

- Remember, neutropenic patients frequently present with fever in the absence of localizing pulmonary symptoms.

- Pulmonary aspergillosis typically manifests as single or multiple nodules with or without cavitation, patchy or segmental consolidation, or peribronchial infiltrates, with or without tree-in-bud patterns.

- In the presence of angioinvasive disease, Aspergillus species can hematogenously spread to the skin, brain, eyes, liver, and kidneys. This obviously portends a poor prognosis.

- To diagnosis invasive aspergillosis, consider initially sending serum biomarkers, such as galactomannan, and obtaining sputum for fungal staining and culture.

- If the diagnosis is not made, more invasive options include bronchoscopy, image-guided needle biopsy, or video-assisted thorascopic surgery.

- The recommended intial therapy is voriconazole, or lipophilic amphotericin B if there is a contraindication to voriconazole.

Friday, July 6, 2012

Life Threatening Infections Associated With Diabetes

Today, we continue with the theme of diabetes mellitus and its feared complications. In particular, we learned about life threatening infections associated with diabetes.

These include:

1) Invasive or "malignant" otitis externa

2) Rhinocerebral mucormycosis

3) Emphysematous infections (most commonly, pyelonephritis and cholecystitis)

4) Synergistic necrotizing cellulitis

5) Pyogenic liver abscess

Some key points to remember about invasive otitis externa:

- Most commonly diagnosed in the elderly diabetic population.

- Most commonly diagnosed in the elderly diabetic population.

- It is almost always caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (around 95%).

- Presents classically with otalgia and otorrhea.

- Osteomyelitis of the temporal bone can lead to palsies of cranial nerves VI, VII, IX, X, XI, XII.

- If left untreated, the infection can progress to meningitis and brain abscess formation.

- The diagnosis is made on the basis of findings on imaging (see below).

- Antimicrobial therapy targets the culprit pathogen, typically for 6-8 weeks.

Bone Scan demonstrating the "ear muff sign" of the right mastoid region.

CT head demonstrating bony erosion of the anterior wall of the right mastoid air cells.

- Presents classically with otalgia and otorrhea.

- Osteomyelitis of the temporal bone can lead to palsies of cranial nerves VI, VII, IX, X, XI, XII.

- If left untreated, the infection can progress to meningitis and brain abscess formation.

- The diagnosis is made on the basis of findings on imaging (see below).

- Antimicrobial therapy targets the culprit pathogen, typically for 6-8 weeks.

Bone Scan demonstrating the "ear muff sign" of the right mastoid region.

Thursday, July 5, 2012

Diabetic Ketoacidosis

In today's Rapid Fire Morning Report, we discussed the management of DKA.

To review, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and the hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state (HHS), formerly known as hyperosmolar non-ketotic coma (HONK) are caused by the combination of:

1) absolute (in DKA) or relative (in HHS) insulin deficiency AND 2) upregulation of counter-regulatory hormones, such as glucagon, cortisol, and growth hormone. This results in increased glycogenolysis and hepatic gluconeogenesis.

The hyperglycemic state leads to osmotic diuresis and intravascular volume depletion. In DKA, the breakdown of triglycerides results in the release of free fatty acids leading to ketogenesis.

Important things to remember:

- It is always important to elucidate the precipitant in order to treat it and prevent further events from occurring.

- The pillars of treatment include intravascular fluid resuscitation (primarily treating the hyperglycemia), intravenous insulin therapy (primarily treating the ketoacidosis), and total body potassium repletion.

- The role of bicarbonate and phosphate are controversial.

Please click on the link below for access to an excellent review article on the Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis and the hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state by Chiasson et al. from CMAJ (2003):

http://www.ecmaj.ca/content/168/7/859.full.pdf

Tuesday, July 3, 2012

...And so another year begins!

Welcome...

To your first day as a physician.

To your first day as a senior.

To a new academic year.

It’s going to fun.

It’s going to be exciting.

It’s going to hard work.

But, you are going to learn so much.

Stayed tuned to this Bat-channel at most Bat-times for a smorgasbord of medical pearls and salient references pertaining to topics discussed at Morning Report, Noon Rounds, and on the Wards.

Today, at Noon Rounds, the topic was an orientation to Code BLUE, where we discussed IO line insertions, among other things. Kindly find below a schematic approach to cardiac resuscitation from the 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support.

Now go out and...

Learn lots.

Be safe.

Don't be afraid to ask for help.

And in the parting words of Hal Johnson and Joanne McLeod, Keep Fit and Have Fun!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)